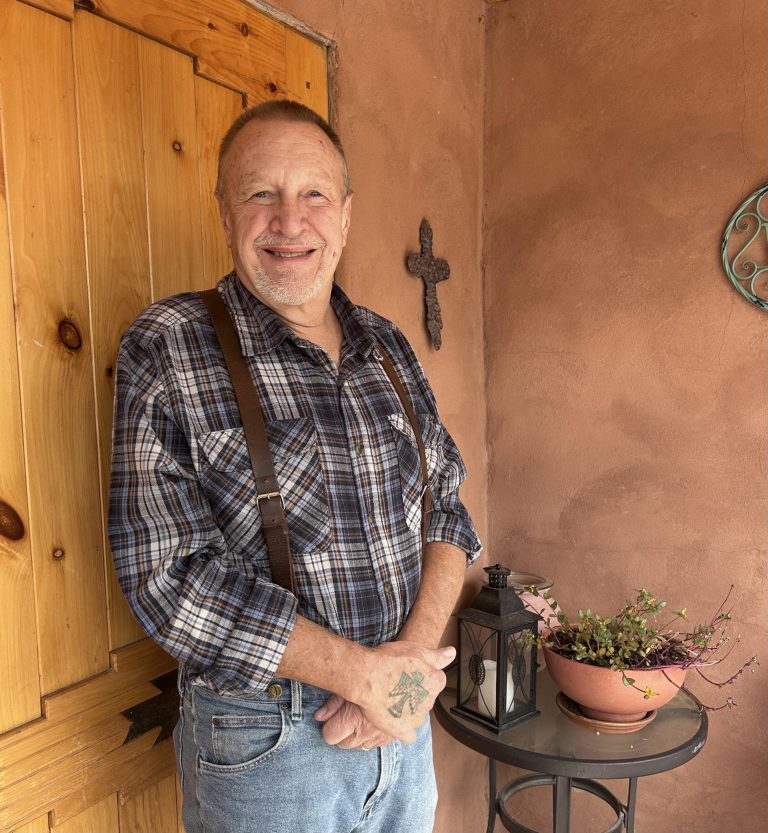

T’Naus Nieto

The Chronicle-News

Eric Treider, who’s running for Trinidad’s City Council, created an expansive and thorough analyses of the city. This includes addressing housing shortages, reducing housing costs, attracting remote workers and tourism and, solutions for the unhoused and preserving Mt. San Rafael and the nursing home amid the upcoming impacts of the “One Big Beautiful Bill.”

Treider is a retired oil field worker of 30 years and a social worker, who has volunteered to support charitable efforts for the local unhoused and taught human services to incarcerated individuals at the Trinidad Correctional Facility through a program from Trinidad State College. He moved here from Alaska after living there for around 35 years.

“Of all the places I could have lived, this is the place my wife and I chose to make our stand. My wife and I love it here. And we want to devote all our efforts to make this community stronger and more united.”

Treider is no stranger to government, having been a politically active person who ran against a ConocoPhillips executive for a state senate seat in 2014, stepping up to run so he could “stand up for citizens.”

He said, “[He] (his political opponent) voted for oil tax laws that gutted Alaska’s state budget, which produced a lot of hardship for our citizens up there and devastated our university system. So, I’ve always been really passionate about standing up for regular folks—against people who might want to exploit them.”

When asked about Trinidad’s local government, he said, “I don’t really see that kind of thing going on down here. But I think what got me interested in getting involved with running [for city council] was the unhoused.”

According to Treider, he and his wife had been getting involved with the community, helping provide weekly meals to the city’s unhoused.

“We have a lot of compassion for them,” he said. “About six or seven years ago, we had been commuting from Alaska to work on this house we bought about ten years ago. And I ran into a couple of homeless people, and I invited them to move in with me.

“The social worker in me kind of came out, and I started doing case work with them. The gentleman who was living with us was probably only a few months out from dying from Hepatitis C, and we managed to get his $80,000 bottle of pills that cured [it]. His wife had some serious psychiatric problems, and we managed to get her patient care.”

Over the course of five months, Treider and his wife grew increasingly familiar with Trinidad’s unhoused population, learning about and understanding the culture and challenges they face.

“One of the things I learned is that once a person becomes homeless, it’s practically impossible to work your way back to mainstream society again. You have so many impediments, lack of transportation, a place to charge your phone in case you get a call, the ability to care for your clothes and your body—there are a million issues.

“In addition, people who face homelessness often succumb to addiction issues; that’s just how they cope with the situation (self-medicating).”

Treider explained that he worked with notable local unhoused advocate Pastor Clay Mason, who helped convince him to consider running for city council.

However, some locals have expressed concerns about the unhoused downtown and how their presence could have a negative economic impact.

When asked about public perception, Treidor responded, “I understand that the public may not feel safe or secure around homeless people at times, and that needs to be addressed. People feel they can’t go out to the park and enjoy it without stepping on a syringe or being unable to use the bathrooms because they’re locked. Business owners feel like the viability of their businesses is threatened by the homeless. There are a lot of facets to the problem. It is a prominent issue, and it is what got me involved in this.”

When asked how the city could address the controversial topic, Treider explained that there could be an approach that would balance humanitarian efforts with addressing economic concerns.

He explained that he had been working with the unhoused systems coordinator, Erica Gonzalaz. He supported the idea of designating a centralized gathering place, an approved camping location for easy distribution of charitable efforts and resource availability, while ensuring the area was an appropriate distance away from the downtown area, which would reasonably reduce economic concerns for business owners and tourists and mitigate parental safety worries at public parks.

When asked if he felt recent city policy and changes had positive or negative effects, he said, “I think it stigmatized them.”

“It makes good business sense to address this issue, in addition to all the humanitarian reasons,” Treider said. “One thing I think many people don’t understand is that the cost of homelessness far surpasses the cost of fixing the problem. The average cost of housing somebody is around $13,000 a year. If you add up emergency room visits, extra law enforcement, and property damage, the cost of homelessness for an individual runs to around $35,000 to $55,000 a year.”

Another key issue Treider spoke on was the potential rural impact of federal bills, such as those proposed to reduce Medicaid and SNAP benefits, which could disproportionately affect rural areas, such as Trinidad, without as much job availability and resources, compared to their metro counterparts, and rural healthcare sourcing much of its funding through Medicaid.

“I think we need to be prepared to step in and help the hospital or the nursing home, because if we lose them, it’ll have a real impact on the community in many ways. It could be devastating,” he said.

Treider addressed another issue, which he said was vitally important—affordable housing.

He expressed that he hopes the city can expand its “housing first” grant program, which uses funds to rehabilitate homes, but wants to see changes to the zoning restrictions to allow the creation of “tiny home villages” and accessory dwelling units within city limits.

Treider mentioned the need for more parking downtown, the police department’s consideration of a community police approach, which could foster better relations between authorities and the community, and renewable energy.

“I’m a big believer in solar energy and renewable energy,” he said. “Our city codes right now actually discourage solar energy, and battery storage is not allowed.”

Additionally, Treider mentioned the urgency of Trinidad improving its emergency preparedness. “There is only a few days’ supply of food to sustain us in an emergency. That could be a challenge.

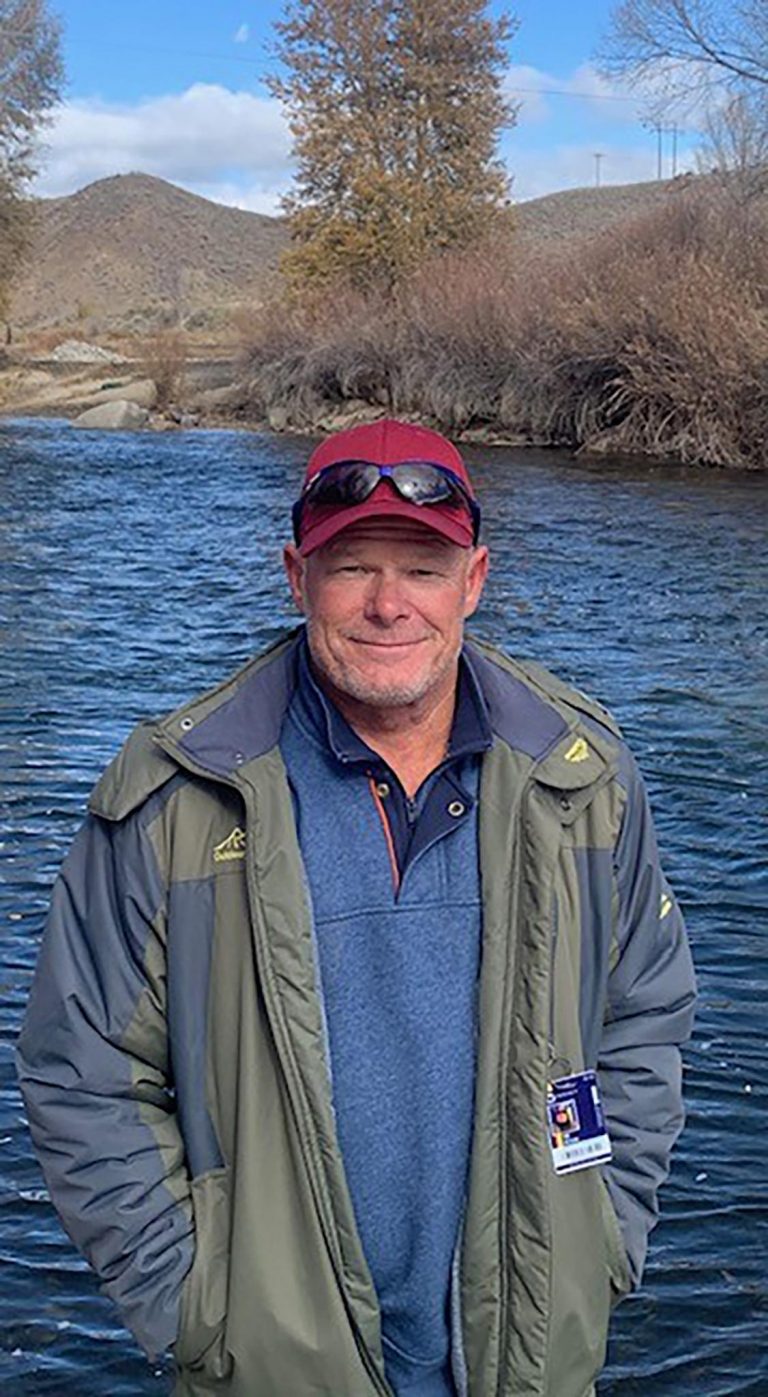

When asked about his view on the economic future of Trinidad, particularly with the idea of the city being an outdoor recreational tourist destination, he said, “I would like to develop more of a reputation for us being a destination for the outdoors, and I’d like to see the trail systems expanded with more camping opportunities.”

Treider expressed his passion for supporting the future of Trinidad and the people who live here, so when asked why he and his wife moved here. He said, “One of the reasons we decided to move here was because the people are so friendly. I grew up in Albuquerque, and this place has always called out to me. And when it came time to retire, I started checking things out here. This place really feels like home to me. I love the mix of different cultures here, and it’s the friendliest place I’ve ever lived. People genuinely seem to care about one another. And I think we need to build on that for what I see could be hard times coming. And I think we need to be there for each other, rely on each other for what could be tough times.”